Art critic, geologist, botanist, Alpinist, architectural theorist and social reformer – maybe even revolutionary – John Ruskin gazes with troubled intensity from a watercolour portrait that dates from when he was on the verge of losing his mind. Half his face is in shadow, the other in mountain sunlight. His blue-green eyes stare almost too intently. There’s something wrong behind them. The following year, over Christmas 1876 in his beloved Venice, Ruskin would start to hallucinate. Breakdowns would follow and he eventually withdrew from the world, cared for at home on a healthy inheritance from his wine merchant father, until his death in 1900.

Ruskin’s manic portrait, attributed to Charles Fairfax Murray but quite possibly the critic’s own work, fits well into the late-Victorian interior of Two Temple Place, laden with rich wooden carvings, panelling and stained glass. Or does it? It’s safe to say its architect was influenced by Ruskin’s gothic vision of architecture. Yet it’s an equally safe guess that Ruskin would have loathed it, for this neo-Tudor fantasy was created for the American millionaire William Waldorf Astor. In his book The Stones of Venice, the bible of the gothic revival, Ruskin denounces the very opulence and selfishness this building represents. Medieval gothic, for him, is an art of communal togetherness, created by a morally superior age that respected honest work and condemned capitalist usury.

And there, in a nutshell, is the reason for today’s Ruskin revival. In the late 20th century, Ruskin was considered a bit of a joke. Even now, his name for many people evokes a sexually repressed Victorian oddball. Even the curators of this loving homage can’t resist telling us how working-class audiences laughed at his “megaphone” lecturing voice and quirky bird imitations. Yet as the deepest crisis of capitalism since the 1930s drags on and Victorian critics of the cash nexus, from Karl Marx to William Morris, are taken seriously once more, Ruskin’s social radicalism looks urgent again. He was ahead of them all. In 1860, he horrified readers of the Cornhill magazine with a series of articles that denounced free-market economics. The myth of a grasping homo economicus, he argued, is a fundamental misconception of human nature. Marx’s Das Kapital would not appear until seven years later.

At the heart of this celebration of Ruskin’s 200th anniversary – he was born in 1819, the same year as Queen Victoria – is a telling story of his generous, ardent spirit. In 1875, Ruskin created a museum for the people of Sheffield. The north remembers: this show has been created by Sheffield’s museums together with the Ruskinian Guild of St George. Art, Ruskin believed, was for everyone. And everyone needs it. The industrial working class deserved not just bread but beauty. The most beautiful thing in this exhibition, however, is not a work of art. It’s the collection of minerals Ruskin presented to his people’s museum. These gorgeous rocks set this exhibition alight with their strong colours and brilliant crystal facets: purple amethyst, snow-white quartz, bubbling haematite.

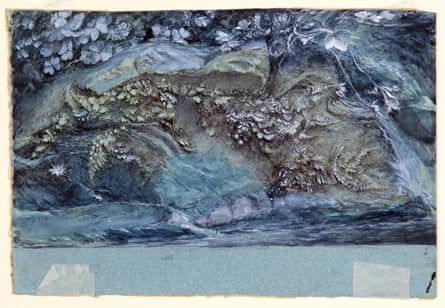

He created his little museum in a former cottage in Walkley, between Sheffield and its surrounding countryside, to draw working folk out of the smoky town to explore nature. For Ruskin, the natural world was sacred. To be in it was to be enraptured, transformed, redeemed. His responses to the natural are on display in his drawings and watercolours of glaciers and mossy riverbanks, wildflowers and a bright blue peacock feather. His eye for nature can be enthralling, especially when he homes in on strange gothic patterns and textures. His Study of Moss, Fern and Wood-Sorrel, Upon a Rocky River Bank is a mesmerising portrayal of green life entwined in the ancient scars and turbulent strata of a steep rocky mass.

Here is another way Ruskin suddenly looks contemporary again. There are new images of nature among the Victorian drawings, including a chilling digital analysis of the changing forms of Alpine glaciers by Dan Holdsworth. Ruskin knew nothing of global warming, but his passionate belief in the preciousness of nature comes through in his awestruck Turneresque watercolour of Vevey in the Alps, with its sapphire, immemorial mountains.

What the show can’t fully reveal, because it is hidden by the precision of his drawings, is the tragedy of Ruskin’s passion for nature. Brought up as an evangelical Christian, shaped by the glories of art and nature he saw on childhood trips in Europe, his vocation as a young man was to teach his contemporaries to see the divinely created beauty of the world. “I have to prove to them ... that the truth of nature is part of the truth of God,” he wrote. As those lovely rocks in this exhibition show, geology was at the heart of his theocratic scientific vision. Yet geology in the 19th century was the very science that was demolishing god, fossil by fossil. By 1851, he could hear the geologists’ hammers chipping away his faith: “…those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.”

Ruskin’s scientific honesty devastated his Christian belief and that may have helped to destroy his reason. His calm drawings disguise a turbulence that was tearing him apart. His socialism, too, emerged in the later part of his life. In the Victorian hymn All Things Bright and Beautiful, the social order is seen as divinely appointed. But if there’s no God, Ruskin saw, why should the poor wait at the rich man’s gate?

This exhibition is a timely reminder of the tortured genius of the most complex and gifted art critic who ever lived – although it shows how inadequate any label is for this lofty soul.